Real Canadian Stories

The autobiography of Gwendolyn Shortt 1903-2002, by Leif Harmsen

I think that if I had remembered anything myself, I would have remembered the boat trip over here and I don't. We landed at Halifax on my fourth birthday. I don't remember. I don't think that anybody can recollect what they were doing at four years old. I think I just heard my mother and father talk so much. Everyone was flocking to Canada around the turn of the century. My father said that they misrepresented what Canada had for people. You would think you could pick up gold off of the streets according to the flyers you would get and what you would read in the paper. I think that if I had remembered anything myself, I would have remembered the boat trip over here and I don't. We landed at Halifax on my fourth birthday. I don't remember. I don't think that anybody can recollect what they were doing at four years old. I think I just heard my mother and father talk so much. Everyone was flocking to Canada around the turn of the century. My father said that they misrepresented what Canada had for people. You would think you could pick up gold off of the streets according to the flyers you would get and what you would read in the paper.

I think I remember when I was still in Wales, going out with my aunt Margaret for fish and chips. They'd peddle them from wagons on the corner just like popcorn wagons would popcorn today. But still I think that when people say they remember all this from when they were youngsters I doubt whether they do. And do you know what they still do in England? They wrap the chips in newspapers. My god! Would you ever want to eat anything out of a newspaper? Something that was fried and greasy and in a newspaper!

Margaret was my mother's only sister. She never had any family of her own. She had her A.T.C.M. in music and her father, my grandfather, had sent for a solid ebony piano from Germany when she got the degree. Imagine what that piano would be worth today! I always gravitated to it. She was very fond of me and apparently I stayed with her often. She begged my mother to leave me with her in England when they came here. My mother had two daughters, Phyllis and myself, and Cecil was already in the oven as the saying goes, when we set sail. I guess my aunt thought that my mother had quite a bit on her plate, and that likely she'd be helping out. My mother wouldn't leave me. If I had been left there I would be a good pianist today.

Aunt Margaret was here in Canada for a holiday after I was married and we were living in Ottawa. She said she just adored Canada. She said "If I were younger, and didn't have my ties..." She just loved Canada. Everybody does. When they come from other countries they just love Canada. There's a song, "Oh, Canada" and there was another Canadian song they had but I'll be damned if I can remember it now. She wanted to be sure that she would get the sheet music, especially "Oh, Canada." She said it was such a beautiful, beautiful song.

My father's motivation for coming over was that he had TB. Of his twelve siblings he had one sister and three brothers that had died of it. His doctor said that Canada would be a good healthy place for him to recover what with no dirt or smog; of course Canada was new then. My father always slept out in a tent as soon as the weather was warm, and he swallowed lots of milk with chopped up liver.

People had a lot of courage. My father was only twenty six. He came out here with a pregnant wife and two kids to a strange country with just a hope that he would get a job. I've often wished that I had asked why my father chose to settle in Picton. We were content there, everybody agrees that it is beautiful country. It was even more beautiful then, before they built the cement factory and tore down the old houses. But why he chose Picton in particular I don't have a clue. When you are four you don't think to ask and when you're growing up it's just where you are I guess.

My father worked at Wilcox grocery store at one time and I can remember seeing him there after school. I can remember the big wheels of cheese, you didn't get little bits all done up in plastic like you do now, and the enormous manual coffee grinder. He was a whiz at office work so he wasn't there long before they put him in the office. He had the right kind of friends. I don't mean that to sound snobbish. We never gravitated to anybody who was uneducated or slovenly. Water finds its own level.

My mother had money. My mother had a lot of money left to her by her grandfather who lived in Dover. He had an antique shop or a second-hand shop or something and had a lot of money. She used to go and spend summers with him when she was sent away to school after her mother died. Apparently they got along just like a house afire and he just thought the world of her. He left everything to her. She leased a house and picked out all of her furniture before she was married, all the drapes and everything else was set up while she was on her honeymoon. I remember my mother telling me about the house in Wales. There was a brick passage with a wrought iron fence and gate at the end by the street. She told me that I used to look through the passage and watch the Redcoats march past on the street. She would often cry when I was a kid; she'd say, "I'll never have a home like I had when I was first married." They had sold everything to come over here.

Everybody trusted my father, Tom Mounce. They used to call him "Honest Tom." He had integrity plus I tell you. I can't forgive him for not getting me a piano but I'll give him this: he brought us up properly. He brought us up with the right values anyway, he may have been a bit tight with money but after all he had six people to keep. There were people in Picton who's daughter was going with a lad that they didn't approve of. They thought he was beneath her; he was just a lower class type. I remember my father saying about her, "If you sleep with the dogs you'll get fleas." As far as living or the people that you choose are concerned he said, "If you're going to step anywhere don't step down, step up."

His boss, Mr. Carter, had a daughter who was a very good friend of mine and I was often invited down to their house. We had a very ordinary house and they had a great big house on the bay. In fact, their big house later became the first hospital in Picton. They had a piano that was something else and if I went down to Carter's I could play it. My father was just an employee, you know what I mean, and Carter owned a quarter of the town you might say. I felt honoured to be invited there; my mother would dress me up in my best clothes and everything if I were going down. Mr. Carter told my dad that he never had any children in his home that were as well mannered as us.

Eaton's catalogue was a big thing for people who lived in small towns or were busy or had children. My mother had four; she had plenty to do and hated shopping anyway. We'd get the Eaton's catalog in the fall and of course all the Christmas sections would be in it. You could buy just about anything. They used to call it The Eaton's Bible years ago. Parents and kids and every one else used to love leafing and seeing. For Christmas I used to say "Oh I'd like that, I'd like that, and my brother and sisters would say "Oh! I'd like that that and that..." My mother said "you can have three things, you decide." The catalog would arrive in the fall and it would take until almost a week before Christmas before we could decide. We wanted about fifteen things and we had to cut it down to three. Oh the dolls that you could get! I had what they called the "Eaton Beauty Doll" and that was a dollar! Boy, that was a lot of money when I was a kid. When I saw this Eaton Beauty doll that was one thing I wanted. It was the most beautiful doll you ever saw in your life; all fully dressed with little white dress, shoes, ribbons in its hair and everything. Every little girl wanted an Eaton Beauty Doll.

Kids years ago weren't exposed to so much. I believed in Santa Claus until I was twelve years old. Then I got suspicious. We had registers that let the air between floors. We'd look down them and watch our parents put gifts under the tree. I remember how we'd hunt all over the place before Christmas to find where mother hid the presents. She must have had a dandy hiding place because we never found it.

Aunt Margaret would always send the nicest things for us kids at Christmas. She sent a pattern to make a raw silk dress for me. My mother got a dressmaker to make it. The top was lacy and the sash was a beautiful shade of blue with a flat bow at the back. I was so proud of my Auntie Mag's dress. One year she sent us hats. They were those little fezzes like they wear in the East, bright red with little tassels on them. We always called them our Turkey Hats. Another year she sent fur lined gloves... We were always so thrilled at auntie Mag's parcels.

I remember I used to be able to recite poems. My memory isn't good now. All a teacher would have to do is read a poem to me twice and I'd know it from end to end. I remember one I did was the Dingo Dog and the Calico Cat, I don't suppose you've ever heard that -

Side by side on the table sat.

It was half past twelve, and what do you think?

Not one or t'other had slept a wink. It was about Santa Clause coming anyway. And then there was another one I liked. I used to dress up in white gauze and I had a mask on because it was a story about a ghost.

I used to be able to sing well. God, I can't sing now. They had the church choir for the month of Mary which was the month of May. Mary was supposed to be Christ's mother and we revered the both of them a lot. My mother would say, "Isn't that nice. They always pick you to sing the solos." I remember our priest used to love our singing. We were very impressed one time. He had a great big bucket made of wood and it was all full of candies.

My teacher taught from age seven until the entrance to high school all in one little room. I often wonder how we could concentrate. We'd sit in our seats and she'd say, "First Class Rise Forward." The first class would rise and go forward to her desk and we'd answer her questions standing. How did we ever concentrate with all that going on? The kids from out of town brought a lunch and stayed at school while the town kids and the teacher went home to eat. One young lad came in ahead of school hours to fire the coal stove up, and then he'd stoke it at lunch. During lunch one day I saw this lad with coal all over his hands and everything else. I said, "Wouldn't it be fun to have a darkie show." We put coal all over our hands and faces and sang and danced and pretended to be blacks. We sang "Massa's in the Col Col Ground" and all those old songs that negroes used to sing - the songs we thought negroes used to sing anyway because we didn't know any. We had a party amongst ourselves. As a rule the teacher was gone for about an hour and a half but that day she came back early. Everybody had got the coal off their faces but me! I forget how, but I got punished for doing that.

There were some ethnic people in town. They had a fruit store wouldn't you know it. What Italian doesn't have a fruit store? Anyway they had I don't know how many kids. When the teacher said, "First Class Rise Forward." The youngest one would stand up and he'd pee down his pants! His older brother would have to come and clean it up. We used to get the biggest kick out waiting for this little kid to pee on the floor. He did it every time.

In those days you had to be somebody with beans in your pocket to have an indoor bathroom. If you went to somebody's house who had an indoor plumbing you'd talk about it for a month. We'd haul in our bath water by the pail full and heat it on top of the stove. The four of us kids had to use the same water. I'd always get the first bath because I was the cleanest. Thora and Phyllis came somewhere in the middle and Cecil was always the last. He used to call it "The Soup."

Cecil was my favourite of all of my siblings because he always got the little end of the horn. Most men, you'd expect, would be very happy to have a son after having only daughters, but Cecil never got very much attention.

Cecil had more dogs follow him home. There was one dog that followed him home, I can't remember what kind of dog it was, but the skin was so loose that you could take a bunch of it up in your hand and you still didn't get down to the dog. My mother would say, "Oh don't let your father see that dog." Finally my father would see the dog and he'd have a fit, "Don't let that dog in at night!" My mother had a great big wicker clothes hamper in Cecil's bedroom. My father would rap at the door, "Cecil?" Cecil would run over to the hamper, take the lid off and snap his fingers. The dog would jump in and he'd put the lid on. "Have you got that dog in there?" Cecil'd say "No." The dog would never let out a squeak. My mother would say, "He's had that dog in bed with him! There are tracks all over the pillow case!" He loved that dog but he told me that it was driving him crazy trying to keep it hidden each night and he didn't want it to stay outdoors. Somebody asked him how much he'd take for it. My mother said, "I think that guy gave Cecil ten dollars for that dog!"

My uncle Charlie, my father's brother, was a happy-go-lucky kind of guy. He was a beautiful baker. He used to make cream puffs and they were full of real cream - not that imitation stuff you get today. After school we'd buy a dozen for fifty cents and they wouldn't make it home. In those days the baker would make the rounds to all the houses in his horse and wagon as did the milkman. One time he walked out our door after delivering the goods and his wagon and horses had vanished. He yelled, "Ere runned away!" He had never had to tie them before. My father never got over that, he'd yell "Ere runned away!" and roar with laughter.

My aunt Clara was uncle Charlie's wife. Not a blood relation at all but boy were we close. They moved to Picton when I was about nine. Clara had only one daughter then, Winifred, and used to say that if she had another she'd call her Gwen. And she did. Gwen Rennie her name is now. She is my namesake. If people were referring to us I was always big Gwen and she was always little Gwen except pretty soon little Gwen was about five foot six in her stocking feet and so they decided to reverse our names. Gwen phoned me just the other night. She just had her eyes done; she had cataracts. She just wanted to phone and wish me a Merry Christmas.

Phyllis, my second sister, no one had any use for at all. You couldn't believe a word she'd say. She'd pick up anything she'd feel like picking up anywhere she'd go; she was light fingered. My parents knew it. My father used to say if she'd go anywhere "Don't touch anything." If she'd like anything she'd just pick it up and put it in her pocket when she was a kid.

Phyllis could pull the wool over my mother's eyes. I don't know if my mother misunderstood Phyllis or didn't want to understand, but she'd make up all kinds of excuses for Phyllis. My aunt said, "Jose, you're aiding and abetting Phyllis in everything she does and things that are wrong." My mother would say, "I think she just exaggerates a little bit, Clara, you see." My aunt later said she hated to say this because my mother was such a sweet person, but she said, "Jose, Phyllis doesn't exaggerate, she LIES!"

My father's mother apparently was the most beautiful woman in the town where they had lived, that's my dad's story. Friends and relatives who knew my mother said that the reason Jose makes such a big fuss over Phyllis is because Tom thinks Phyllis resembles his mother, and she was doing it to please him.

Whenever Phyllis got new clothes my mother would stand at the window and watch her walk up the hill into town and say, "Oh come here - Oh doesn't she look lovely!" The first time my Aunt Clara made me a dress it was to go to a party. Of course I thought it was wonderful. I knew I looked nice, sure, but I wanted the approval from my parents. I said to my mother, "Well, how do I look?" She hit me a slap on the shoulder and said, "You'll pass with a push." That's what I got while they just drooled over Phyllis all the time. Thora said, "It's no wonder we hated her guts, she was the only one they made a fuss over, all the rest of us were pushed aside."

Phyllis used to say to me, "How come you have all these friends?" I said, "If I have a friend I have a friend." I've never had a friend that I've ever fallen out with. I said to her one day, "You have to be a friend to have a friend." She wouldn't be a friend to anybody. She was just cutting her own throat she was so mean.

I remember some friends we had and I adored them. The Shannon's. They used to drive us to church in their big carriage with a hood and a little fringe all around the top. I loved that fringe. When a few people started getting cars the horses would freak out. We'd hear a car coming and Mrs. Shannon would say, "Oh god! Get out and hold the horses." If Mr. Shannon didn't, the horses would rise up on their hind legs and go "Neahehehehehe!", an awful sound. And so he did.

The Shannons couldn't really complain; they were the first people in Picton to have a car if you could call it that. It was a strange contraption without a top, just for touring really. The horn was this big bulbous thing that you'd squeeze and it would let out a honk.

To visit the Shannons was fabulously entertaining. I've always loved music. She played the piano and he played the violin, and as though that weren't enough their maid could whistle. Boy could she whistle. Today she could get jobs in nightclubs with such talent. The three of them were just something else.

When I was about fourteen we bought a new house near the centre of Picton. It had all indoor plumbing and we thought it was wonderful; we didn't have to get our feet wet on a rainy night. It was built high up into the cliff over the harbour. It had a great big porch that opened up off of the dining room and from it you could drop a stone right down into the Bay of Quintie. It was lovely, you could see all the boats going by, back and forth between Brockville, Montreal, Picton, Toronto, and Kingston... They'd all have different articles that they were taking. Huge big lake boats used to go up and down. It was nice. I'd say "If I'd ever get married I'd want a house on the water and a fire place. A fire place was the only thing we didn't have.

We had a wonderful garden with all kinds of fruit trees. We had a plum tree laden to the ground. We had lots of apples, Snow apples, Belflour apples, Resset apples, Macintosh apples... I can't think of all the names now. You never see all the varieties we had then, and nobody was spraying like they are today; I never thought the chemical spraying was very good. I like a good Spy apple for to make a pie or just for eating. I love the smell of a pie made with Spys. You know I never see Spys any more at the A&P or Lawblaws. I never cared for "Delicious". To me they're not delicious at all. They're a nice looking apple with the little dimple in the bottom. Everybody raves about Delicious apples. Well they can keep 'em.

We had a cat and it had oh I don't know how many kittens. We'd ask around, "Does anybody want a kitten?" And everyone said, "No. We've got a cat. We've got a cat." My father said, "We're not going to have these damn kittens around." So he got an old bran sack, put the kittens in with a rock and tied the top of it, went out on the porch, swung it around his head, and heaved it out into the Bay of Quintie. Well. The sack broke and the kittens all swam into shore... but they never came back to our place!

What did I do when I got to be a teenager... I got a catalogue from Belles Hes of New York City. I don't know how the heck it had come to us. All the things in it were cheaper than Canada and so nice. I used to buy everything from Belles Hes. There was duty on it but not very much. I remember I got the most beautiful coat. It was just the colour of a dark plum. It was just a rich looking thing. It has a lovely great big collar on it that almost looked like fur; it was some kind of plush or something.

My mother knew the head milliner in Bristol's. Hats used to be hand made and the milliner said, "Your mother hasn't got to see a price tag to know quality. Anything she picks for you I'll say, 'Mrs. Mounce, that is the most expensive one on the table.'" She got a hat and I think it was fifteen dollars which was a hell of a lot of money at that time. It was a beaver, a furry thing that was a soft grey colour that looked great with the plum coloured coat. It had a wide brim and had streamers of heavy corded ribbon. Oh gee I thought I was the berries when I wore that hat.

Through the years I've felt guilty. We had a great big cook stove in the kitchen proper but summers it was too hot and we used the little oil stove in the summer kitchen. My mother was mopping the floor and had the bucket sitting on the bottom step of the three between the kitchens. Who came running down but me, all dressed to the hilt and ready to hit the town. I stepped in the bucket and fell flat on my face and the muddy water fell all over me. I stood up and yelled, "You Old She Devil You!" She was mad. I shouldn't have said that.

Mother and I never saw eye to eye. I'd always be dragged off to church and I didn't want to go. People didn't fool around with kids in those days. They had what they called a cat and nine tails and it hurt. She'd chase me around the dining room table. Aunt Clara would say, "You and your mother just don't speak the same language." It came down to making deals. I'd go if I could wear my bright red Organdy dress regardless of how inappropriate it was. My aunt got a kick out of my issuing ultimatums. She'd sit and roar, "Oh Gwen, you're something else!" I was a rebel.

My mother was Irish Catholic. She really thought that her religion was the only one. It never really made a lot of sense to me. I refused to believe that the Pope was infallible. I said, "He's just a human being." We'd have horrible arguments. She'd always refer to the Catechism which is just bits and pieces clipped from the bible like you would coupons from the paper. I said, "If father Carson would tell you to jump in the lake you'd jump wouldn't you?"

If any boy I went with wasn't Catholic, my mother would be thumbs down on him. She'd say, "I don't ever want to see him around here again." Well, all you have to do is say that to a girl that age and they won't bring them home, they'll meet them some place else. And that's what happened. I'd say, "I'm going over to Martha McGowan's to spend the evening." I'd have a date with a Protestant lad. He'd meet me at her home instead of my own. Anybody who wasn't Catholic was no good in her books.

I had an ally on my side. My father had grown up Protestant but had to promise to have his children raised Catholic in order to marry my mother. Of course he'd never say very much, I guess he didn't want to make any waves.

Prince Edward County was just beautiful. If a young man wanted to take a girl to a nice place they'd go to the Sandbanks Hotel. It was a magnificent white frame building with a grand porch. Every Thursday they had dances there. As a rule we'd swim and picnic on the beach by the sand dunes and then go to the dance later. I saw a man there once who was exceedingly handsome- and his eyes - they - had such a life in them, such a spark. He danced very well and I yearned all night for him to ask me to dance. Years and years after I was married I met him briefly and he came right out and said, "I had wanted to ask you to dance, but you were so beautiful that I was afraid to." That was the best compliment I've ever had.

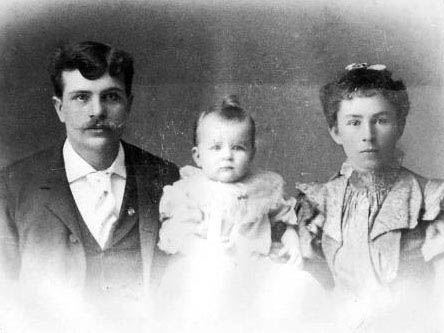

My parents had a picture of grampa Mounce looking stern as though to say, "Don't muck around with me..." He was a regimental sergeant major. My mother said, "Boy, he brought up his family like a regiment too." Apparently I had a stern visage as a child. I don't think I do now. My mother said, "You're the only stern one of the lot; you look just like your grampa Mounce." Apparently she never liked her father in law.

My mother was going on about this when I had a boyfriend there. He said, "Yeah, and I guess she acts like her grampa Mounce too." And I said, "What do you mean?" And he said, "I remember when your girlfriend Myrtle was sick and her boyfriend asked you out to a dance and you said that you weren't going to go out with him because he was your best friend's boyfriend. Then when the dance was over we all piled into the car and he reached over and tried to give you a kiss and you slapped him across the face!" I guess he thought that I took after my grandfather because there sure wasn't any mucking around with me.

Cecil had a tiff with my dad when he was sixteen. I don't know what about; I wasn't home at the time. He ran away and got a job on a schooner. He loved sailing and I remember how thrilled he was when they made him First Mate. He gave that up when he had to get married. She was employed at a candy factory some place. She noticed that he was good at plumbing so she coerced him into plumbing school and then he started in for himself with very little. When Cecil was a kid he'd buy a broken bicycle for 50 cents, fix it up, and sell it for maybe three or four dollars. It didn't matter what he did, he'd make money off of it. He had a good head for business. What with big contracts with Loblaws and what have you- when he was 44 he had enough money to retire then and never work another day in his life.

My father and my uncle Charlie went overseas after the First World War started. My father wanted to be sent to the trenches with the other men, but he was too valuable. He was in the trenches for only ten days when they called him back because they needed him as an accountant in London. As a boy Tommy had twelve siblings when his mother died. His father, who was busy running his bakery, had brought up the herd by sending them all to work. Tommy had taught himself steno and typing when he was twelve years old. He was always interested in education. He was self educated and valued education. He hobknobed with refined people without any difficulty. He was promoted to Secretary to a Brigadier General and apparently the two of them got along like a couple of schoolboys. They were invited to all the best places and he made a good salary.

I spent a lot of time with my aunt Clara during that time. We got along just like a house afire. She was very fond of me. If I'd go there for a meal she would say, "What would you like?" Whatever I liked, that's what we'd have.

I do remember that I never fancied the yolk of an egg. My father would put the egg in the egg cup, then he'd break the shell and take the yolk out for me. Today I can't eat the yolk of an egg. I can eat it if it is beaten up in something but not just per se; not just the way it arrives out of a shell. Even if it's cooked, I just can't stand the stare of the yolk of an egg. At home there had been six of us so my mother couldn't go around asking everybody what they liked.

Aunt Clara used to come up to our place a lot while Charlie was away. We had a house with a big lawn and in summertime we used to eat outdoors. She had two tiny kids and my mother had us four so she figured, "It's easier to ask Clara and her two down here than get you four all ready to tramp up there."

After dinner Aunt Clara'd let on that she had forgotten her house key. She'd say, "Oh! Jose, I've lost my door key." And my mother would say, "Well, where did you have it?" And Aunt Clara would say, "I had it in my purse..." and actually she'd have stuck it in her pocket while she let my mother go through her purse. Then she'd ask to borrow me so she could hold me up to get through a window so I could run around and open the door from the inside for her to get in. She'd go through all that just to have me up there to stay with her. I would love it. But she never wanted Phyllis in her apartment. My mother said, "Why don't you take Phyllis once'n a while?" And I remember this: my aunt would say, "I don't want Phyllis. I want Gwen." She couldn't stand Phyllis. She said, "I can't stand that kid."

I worked weekends at a department store called Bristol's which was the nicest store in town. All the gloves and what not were kept in drawers behind the counter so I went in and the girl in the department showed me where things were kept and I would say, "Thank you very much for showing me." Phyllis decided that she wanted to work there too. She talked to the personnel manager and she got a job. When they were showing her things she would say, "Look, I'm not stupid, I can find things by myself." The clerks couldn't stand her. She lasted two weekends and out she went. Mr. Bristol, the boss of the whole shebang, said, "Is that Mounce girl that just came in recently of any relation to you?" I told him that we were sisters. He looked at me and said, "I can't believe it."

During the War there was a famous dance pair, they were a husband and wife and they were very clever. Girls always had long hair but you were just starting to hear about getting it bobbed. Hers was bobbed and when she was asked about it she said that by not needing hairpins she was saving metal for the War effort!

I wanted mine bobbed. I told my aunt that I didn't want to be the last one. I figured it would be the fashionable thing to do so I had asked my mother but she wouldn't hear of it. I lied to my aunt about that and she cut it. In retrospect I'd guess my aunt must have figured that I was lying. She took the beautiful long locks of hair and put them in a bag and I didn't know it but she brought them to my mother that afternoon, probably to calm my mother down before I got home. When I did my mother was so mad! It was like running into a buzz saw.

There was a woman in town who owned a candy store and I liked her a lot. She had a beautiful diamond ring and she let me wear it to a dance once, my fingers are so tiny so I had to tie it on with string; she must have liked me a lot too. She was angry about my haircut. She said that she always loved my hair, she said, "...but I didn't want to tell you. I thought it'd make you vain."

When I was seventeen my aunt Clara started to make evening dresses for me. My father would be hollering at me because in his day nice girls didn't go out with young men until they were eighteen. My aunt helped me out: I'd often dress down at her place. She'd make me dresses without sleeves which was one of the things my mother would never stand for.

Years ago the only bras you could get were just a piece of cotton with hooks at the back and you could only get them in a horrid colour pink. The boy's figure was popular then and so they flattened down your chest tight. It was an awful thing to make a girl do but I guess in those days you weren't supposed to have a chest. I used to hate those damn cheap pink cotton things. My aunt was way ahead of her time. She used to say that young women have such a lovely chest line. She made this dress for me it had a bandeau thing and a bouffant skirt. I said, "What'll I do? I can't wear a bra with this thing. It has no sleeves." and she said, "Don't wear a bra, you look beautiful just the way you are."

This was the night that I first danced with Jerrold. There was a dance and he had come stag. Maybe a dozen boys would pile in a car together and drive down to the big armoury where the dances were held and they would call it going stag.

We'd had this thing planned for ages, I had a good evening dress and was very anxious to go but my current boyfriend was sick. A friend of mine, Marilyn, and her boyfriend were going and they asked me to come with them. I said, "Well, I don't know..." and she said, "Oh for heaven sakes, come on, you'll have a good time. You know everybody's going there." Well I did. And they were.

It was just before the last waltz. I didn't have a boyfriend with me so I was going to go to the ladies room; I sure as hell wasn't going to be seen waiting around for someone to ask for the dance; I was getting the hell out of there. I was leaving the floor and was almost at the back when Jerrold walked up and said, "May I have the last waltz?"

Any other time I'd have said, "Thank you very much but I'm going to do this or do that." But anyway I kind of liked his looks. He was a well built man and he always used to dress in the height of style; his uncle was a tailor in New York. He had beautiful hair when he was young. He had big thick curls. He used to sign his letters, "Sincerely, your prize with curly hair."

He told me years later, "Let me tell you something, I bet you'll get a laugh out of this. I thought you were the only girl at that dance who looked like a girl, you had such a beautiful, beautiful chest line." And this coming from a farmer! I told my aunt this and she said "Ha, smart boy."

Jerrold had a Model T Ford. Apparently he had had a Harley Davidson before that but he had driven it off the end of a dock into the Bay of Quintie. He was always interested in mechanical things. He told me the story of how he came to get the car. His father had sold two cattle, gone up to Toronto to the Exhibition, saw this new car on the floor, thought it looked nice and bought it. They had shown him how to drive. In those years you didn't have to get a permit. There was no glass in the sides of the cars, that came along later. You'd clip curtains on if it were raining. At the Ex they hadn't shown him how to put the thing in reverse, so the morning after having parked the thing in front of an inn he had to get the inn keeper to back it up for him. It had taken him three days to drive it down to Picton. He had left it out in the lane way and said, "Jerrold I bought something for you in Toronto." Jerrold had said, "What is it?" And his dad had said, "Come on out and have a look at it." Can you imagine a sixteen year old seeing a Brand New Car... I guess he was nearly out of his mind. Gasoline in those days was just a dangerous waste from making coal oil for coal oil lamps, so he'd go to the factory and get it for free. They never had to have it repaired; he could repair it himself. He said, "I have the first car with a self starter and wire wheels in Prince Edward County." And he did.

I dropped the other kid I was going with and I started going with Jerrold Shortt. I worked weekends for a law firm then. My boss, Malcom, heard that I was going to mary a farmer. He said, "What are you going to do on a farm! What's he going to do with you? Set you up on a mantle?" I only weighed ninety seven pounds then. I was very small.

One night my dad said, "Mr. Alison is here to see you." And I said, "What does he want? I remember I'd met him at a dance. We didn't have a phone so I asked him how he knew where we lived. He said, "Oh, I'd ask around town and they told me where the Mounces lived... is it too late to go to a movie?" And I said, "No, I guess not." So we ousted ourselves to the movie.

Is it possible to like two men just the same? I liked them both an awful lot.

Jerrold didn't know my friends in town. He lived seven miles out at a farm and was only in on weekends. Ralph Alison came from a prosperous farm but was working for the Bank of Nova Scotia. He was very bright. In school he was a "Gold Medallist". He was living in town so knew the folks I grew up with. I started going with Ralph steady. I was going with Jerrold on the weekends and going with Mr. Alison during the week. They didn't know about one another.

Ralph rented one of the boat houses along the harbour and had his canoe and his little canoe sail there. We used to go out canoeing after dinner in the summer time. Here we were paddling or sailing around the bay and neither of us could swim a stroke. It was wonderful. I remember us saying, "Well, if we drown we'll both go together."

Ralph and I were down at my aunt's one night for supper. Winnie, my cousin, was playing the piano and Ralph and I were dancing when we heard a rap at the door. My god! When my aunt opened the door it was Jerrold standing there! He came in and I introduced him to Ralph. He said, "I just came into town, I was wondering if you wanted to do something. Are you going to come with me?" I didn't say that I was going to go with the guy that brung me but they were words to that effect. Poor Jerrold. He was only about twenty-two then. He said that he thought that he was going to shoot himself at first. And then he said that he was going to go way up north somewhere in the wilds some place and start a chicken farm. Well anyway, it finally ended up that I gave him back the gifts he gave me and it was ended.

I got engaged to this other chap, Ralph the banker. At that time a lot of men couldn't get married until they were making a certain salary. If you were an accountant you'd be alright, they made 1500 a year. If you were only making 1200 as a teller you'd be thrown out if they found out that you'd gotten married. Ralph was moving out to another town to become an accountant. My father was talking with the manager in town who said, "He'll have no trouble, he'll have a branch of his own pretty soon." He was going to come back and we were going to get married in the summertime.

Anyway, Jerrold kept on after me. My mother would say, "Jerrold's been up here asking about you." If I met him at a dance he'd always have come stag. He'd tell me how good I looked and ask, "How are things going at the office?" I'd be polite and try to get away. My friends said, "Gee, we think he's just wonderful! It's a wonder he even bothers lookin' at ya." We had dance cards in these days. You wore them on your wrist with a little pencil. I remember Ralph had said, "Gee, does Jerrold have a heck of a lot of nerve taking two dances in the first half and two dances in the second." And I said, "Well gee. What's a gal supposed to do?"

Ralph had a pain in the back of his neck that he complained about from time to time. I turned out that he had contracted tubercular meningitis. One afternoon he went upstairs to lie down. He fell unconscious. He was right out of his skull. In two weeks he was in his grave. If it had been today he would have lived; so many people died too young of things that they can manage today. I was just nineteen, still a little kid, I didn't know who I was. I thought that the end of the world had come.

There was a chap who came up from New Brunswick to take Ralph's place at the bank. His first name was Art and I can't think of his last name now. I met him and was out with him four times when he asked me to marry him! He was a nice boy and I've never danced with anybody who was such a good dancer in my life. Everybody would say, "Isn't he a wonderful dancer!" I went with him for about six months while Jerrold kept asking me to go on dates. And I'd say, "I'm still going with Art and we have a date for this and a date for that."

My mother would say, "Oh! Jerrold is such a nice boy." She knew he wasn't a Catholic but I guess she figured that she could convert him and have another jewel in her crown for when she died. The whole family loved him. I said "Gee, the family just takes over that guy when he comes in." Thora was the youngest, she was only about nine then. She'd sit on his lap and he'd read her the funnies. I had some autographed pictures of Ralph and she used to take them off of my wall and you know where I found them? Down in the coal bin! She said, "Art is so little! Jerrold looks more like a man."

I was at a dance once and Clifford Colier came up and asked, "Do you think it would be safe for me to ask you for a dance?" I looked at him, "Safe?" Apparently he had phoned for me once and Thora had said, "She's going with Jerrold." and hung up on him.

Finally Jerrold pinned me down. He said, "What are you doing Sunday?" Canoeing was a great thing then for the young people. We used to paddle down the bay. I said, "We're going down bay." as we used to call it. And we did. He asked a second time for me to marry him. To tell you the truth I felt so bad. I thought I'd used him so awfully and made him so miserable. I felt sorry. I started going with him again. That was about a year after Ralph died.

Jerrold was at our place New Years and he got in the car to go home and it wouldn't start. And I said, "So much for your fancy self starter! You're going to have to stay here tonight." My mother said, "No young man is going to sleep under this roof until you're married to him." He stood out there in the freezing cold, cranking away, and finally got the thing going.

I had met all of Ralph's uncles and brothers and cousins and so on at his funeral. His brother Roy lived in Pulaski, New York, and they asked me over one summer. I had never been to the States and I thought, "Oh that's great. I'll go to the States. That'll be a wonderful place." I went over in July. Jerrold used to write letters, "When are you coming home? When are you coming home?" I got a letter every day. If he missed a day they'd say, "Awe, he doesn't love you any more." The next day maybe a couple of letters would come. Everyone was always laughing about this guy who was sending me letters every day. Roy was the manager of the Niagara and Lockport Power Company and he said, "Why don't you stay, I'll give you a job in the office." They said it was terrible, my going to marry a farmer. He said, "You'll milk cows all your life and you'll have big knuckles and a raft of kids..."

I had told Jerrold that I was going to be two weeks and I had already stayed a month. I wrote him that I was staying. He wrote back that If I didn't come home he was going out west for the harvest. Young lads would often do that and make quite a bit of money. I wrote back, "Well fine! I haven't any money saved up and neither have you. That'll work out great!" God... I was sitting on the veranda one afternoon and this car pulled up. There he was, just sitting there. He was tired of waiting. He came over to get me.

Anyway, the arrangements had already been made. We drove up and took the ferry to Gananoque where his uncle met us with a Cadillac and a friend of his to drive our car back for us. Jerrold had already bought the ring and the licence. I bought a wedding suit and we were married Saturday in Kingston. There I was, married at nineteen and the farthest I'd been was fifty six miles away from home.

Do you know what I eventually did with my wedding suit? During the second war they were asking for clothes and what not for the Russians. I sent it to Russia. How about that.

I had to tie my wedding ring on with string because it was too big. I brought it back to Ports and they said that it was the smallest wedding ring that they had ever sold. We stayed overnight in Kingston at the Randolf Hotel. I hadn't even heard of sex. You can imagine how frightened I was. Then we went up to the farm. No honey moon. No nothin'.

When the news came that I had been married in the Protestant Church my mother cried for days. She was crying into a bath towel that Sunday when we arrived. She would never believe that I didn't have it planned. I said, "My God! You can ask the Alisons." My father had taken Thora trolling way down to Hay Bay in the new motor boat while mother was in such a state. "You've deserted your church and your God." Poor Mama, she was really devastated.

My mother said, "He'd do anything for you." She wanted me to make a Catholic out of him you see. I took him to church a couple of times. I could see he was unhappy. He said, "I don't know when to stand up or sit down." She said "You know he'd do it for you." And I said, "That's bribery! My god, they're Lutherans."

She said, "You'll get killed. You'll have an accident, You'll get killed. You'll get paid out for it. Something awful will happen." In other words the Lord was going to get me eh? It scarred the hell out of me. At that time I was only twenty years old. I didn't quite believe her but it worried me.

I was going to get a dining room suite with a round table as a wedding present. I never got a damn thing. Dad came down to the shower and he brought me a tea kettle and a bread board.

I moved out to the Jerrold's family's farm and it was like going back in time. There was no bathroom or electricity and in the winter I'd have to start up the wood stove first thing every morning. It was sort of a bit of an experience sort of. It didn't bother me too much but I don't think I'd have liked a lifetime of it.

Jerrold's father was working for General Motors in a factory in Oshawa at that time. His mother and his brother Claud were running the farm. She said, "Now that you're here the boys will have a woman to take care of them." And she up and left for Oshawa to be with her husband.

There was no electric iron down there. I had to use one of those heavy flat irons that you'd heat up on the wood stove. I started to iron a table cloth one day and it just bunched up in a heap. I looked at it. I didn't think it was the iron. I said to Jerrold, "I want to iron a table cloth and it just scrunches all up." And he said, "Let me take a look at the iron... Oh! That's the one we used to crack hickory nuts with." Anyway, I went out to the back door swearing, "The damn thing..." And I heaved it as far as I could, clear over the ten foot high wood pile. Claud came out from behind and said, "My god! What's going on here! You could 'a killed me!" Oh! Anytime I'd see him he'd say, "Have you been throwing any flat irons around lately Gwen?"

If Jerrold'd be going out to the barn and I'd be going too, he'd carry me on his back. Many pounds later we were laughing about the farm and I said, "How would you like to carry me on your back?" And he said, "Oh not today."

I couldn't count the times I've polished the lamps out at the farm. I'd always rinse them out before refilling them with oil. Their chimneys would get all smoked up so I'd wash them in warm soapy water and rinse them. I was so proud of those lamps. I used to have a lamp shelf so I could look at the lamps all shiny and nice. People used to be more house proud. Women never went out to work; they put everything into the house.

I remember Christmas morning at the farm. My mother had come down for breakfast and had brought some fancy little things for everybody's place settings. They were little baskets with flowers in them and they were all made of sugar. I ate mine and I was fine but Jerrold got sick. Whatever was in them, well, he must have been allergic to it anyway. He was sick for the day and there was an important job to be done. I wondered if I could do it. I went out and did it. My father later said, "I'd sure like to have seen you, shovelling manure out through those square holes in that barn!" It wasn't the nicest job. It doesn't smell like Channel Number Five, that's for sure.

I'm telling you ice boating is exciting. It was the fastest man could travel in those days. Jerrold built this iceboat himself. You'd just lie on it flat on your stomach. I didn't know what to wear. I borrowed his brother's pants that were all suede and a pair of brown oxfords. I wore a pair of heavy socks, a couple of sweaters, a sweater coat, and an old fur coat of Jerrold's. The winters we used to have were awful. They were cold. We were on our way to the boat and I had to go to the bathroom. And I had all this stuff on me! We'd go like the devil on the glare ice. It was scary. I said, "Oh my lord! What if another iceboat came along?" He said, "God there isn't anything here for miles." The wind would just lift up the front of the boat and you'd go BANG back down again on the ice. Oh I got sick to my stomach and was all shaken up. I never went again.

He made money with that iceboat. He had a contract to bring the mail to Deseronto. In the winter that's the only way you could do it. Once he was taking apples to sell to a store in Deseronto and he hit a bump. The barrel of apples flew off and broke and the apples just went! When he got home he said, "I think they're going yet."

Sometimes we'd go skiing. We'd say we were "skiing" and nobody knew what skiing was. It was something very new. There were no outfits or anything; you just had to whomp up something to wear. You couldn't buy skis in stores. Jerrold's and mine were hand made by a carpenter in Picton, Herb Daubney. He was an artist with wood.

One morning my brother was down helping me cut the logs after I had been out helping milk the cows. Jerrold had a portable manual milker. I used to run the machine but it didn't get all the milk out of the animals so he used to strip them by hand after. We all came in and I made scratch pancakes. I had wool socks on and a pair of heavy leather shoes but my feet were nearly frozen. That farm was cold! You could swing a cat under every door. I kept a big plate stacked with pancakes on the table. I used up all the batter and finally came out to sit down to eat but they had eaten every one! I said, "YOU PIGS!" I remember I turned the coffee pot upside down onto the red hot stove. Oh the stink of burning coffee grounds! I went upstairs and I cried my eyes out and I went to bed with my shoes and all my clothes on. Oh! I remember how mad I was.

I remember Mrs. Shortt was asking me how I got along at the farm. I said, "Not too badly except for the episode with the iron and the one with the pancakes." She laughed.

Jerrold and Cecil used to cut down great big logs on the farm and bring them up with the sleigh and horses to the sawmill. Once they went out with the sleigh and came back with a great big sleigh load of everything you could think of. I remember saying, "What's in the sleigh?" It was covered up in a tarpaulin. Cecil said, "Oh it was raining and we didn't have a coat so we went into this cottage and looked around and I said 'there were some nice things here, eh Jerrold?'" They had mirrors, they had cups and saucers, they just cleaned out that cottage. And I cried and cried and said, "Oh for god's sake take it back! Take it back! Take it back!" Well he didn't.

This went on for quite a few months, then we heard a rap on the door. It was right in the dead of winter. It was a Mountie. He said "Are you Jerrold Shortt?" And Jerrold said, "Yeah." The Mountie said, "I'd like to speak with you for a minute." He was going to take him right away to the station. I started to cry and I said, "Oh, what'll I do?" It was the middle of winter and I didn't have anywhere to go. I couldn't drive a car or anything. I was twenty years old and knew about as much as an eight year old would today. The Mountie said, "Well..." he said, "Well if it weren't for the little woman I'd be taking you in tonight."

Jerrold used to wear a pair of leggings. They were beautiful, they looked like solid leather. They went right up to under his knees and he'd wear them with his pants tucked in them. The Mountie had just gone out the door when he pulled off his leggings and you know where they went? Straight in the fire. I guess he must have stolen those too.

He got a court notice and he was to go to court in Napanee. I remember him crying, and he said, "If I had done what my wife wanted me to do, I wouldn't be in this jam now." The case started in the morning and there was a police man who took us out for lunch. He said "I'm tell'n ya right now Mr. Shortt, you're lucky. Your wife is a real little brick." A real little brick... god there was an awful lot of dirt through the years.

I shouldn't say that I was happier after he died, but for the first time in my life I don't have to worry about what he'd do next. And I never do. I did more crying than laughing while I was married. I didn't have much to laugh about but I was too proud to tell anybody, not even my own parents. I guess I had held him in too high esteem. I felt very let down. I was so ashamed. I still had a picture of Ralph. I couldn't throw it out but I couldn't keep it either, so I stuck it underneath the linoleum on the back stairway at the farm.

In the early spring Jerrold's father quit the factory in Oshawa. I don't know why. Something must have gone wrong or maybe he just couldn't hack it. Anyway he came back to the farm. There wasn't enough on the farm for two families to live well. Jerrold had a cousin in Rochester, New York, who had a lot of clout. We wrote them and he got Jerrold a job down there.

Jerrold's cousin and his wife were wonderful people. They had lots of money and helped us out no end. She and I went out and hunted up an apartment and she'd often take me shopping. They treated us royally. That's how Jerrold got started working in the automotive trade.

I was pregnant with Douglas when we went there. I just asked a neighbour, "Is there a doctor anywhere near?" And she said, "Oh yeah, there's Dr. Colgan up the street." There was something queer about Dr. Colgan; he always had his elbow on his desk and his head in his hand. I didn't know about doctors or gynaecologists or anything else.

I came darn near dying when I gave birth. I went through twenty eight convulsions, one every hour. One can take you out of this world. The priest was called in to read my rites. I remembered what my mother had said about me getting paid out for marrying a Protestant. Again, I didn't really believe it but it scared me. I was ninety seven pounds when I got pregnant and I had a ten pound baby. We found out later that Dr. Colgan was a drug addict.

Before they sent me home they took me up to the nursery and they showed me how to bathe the baby and what not. There was a great big fat Jewish woman there watching as she waited for her baby's turn. She said, "How old is that child?" And the nurse said, "He's four weeks old, that's his mother over there." And the lady said, "That little wee girl? A big slob like me has a five pound baby and she has that! That's cruel!" And it had been.

I loved Rochester. We bought a great big black Overland Roadster with a rumble seat so Jerrold could drive to work and we could visit friends. I don't know how the authorities found out about Jerrold being on probation but they did and we were deported. The whole thing threw me maybe more than it should have. They escorted us as far as Black Rock at the boarder and then we were on our own.

When we got to the farm Jerrold's mother had put all new linoleum on the back steps. I really respect her. I knew she must have found Ralph but she didn't say a word about it to me. Nor I to her.

I hated Oshawa. I don't know what it was. Rochester had been a beautiful city and this was just a working man's town. You'd see men going along with their lunch boxes, dressed kind of rough looking. I'd go shopping with a neighbour and we'd wheel our babies through the dust. Those first 5 or six years were really hell. I just didn't like it. We were running so near to the line. Jerrold had a job as an apprentice mechanic and Sundays he used to get twenty five dollars for each new car he'd drive down to dealers in Ottawa. I couldn't drive then, Jerrold said that I wasn't the type to. I wish I could have; we could have doubled our money.

We learned to play Bridge in Oshawa. That was 1925-26 I think, long before Contract Bridge anyway. Option Bridge was all there was so we didn't get a penalty for not meeting a contract. We played with a four table club and we'd have "Supper Bridges". I think in Oshawa we played Bridge out of boredom, but I got so I liked it. I was damn good. And do you know who was even better? Jerrold.

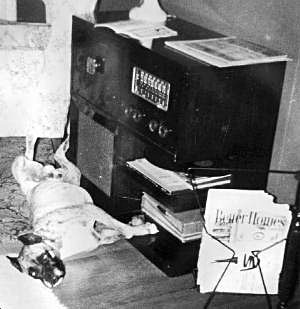

Radio came along when we were in Oshawa. The first radio we had was huge and had a great big horn on it. It was a big deal if you could get Manitoba or way out West some place. Oh you'd brag the next day. Years later Doug wanted his own radio, so we told him to ask Santa. Years ago they had crystal sets. They were little tiny sets. You could pick them up very cheaply. Doug was just expecting a crystal set but instead we bought him a nice little portable radio. He nearly went out of his mind.

I came with Jerrold to Ottawa once and I met this one dealer and he insisted that we stay for dinner. He and his wife took us all around the city and showed us everything. I liked it. I knew Ottawa was the place for me. I remember saying to Jerrold, "I'd love to live down there." Six years later Jerrold got a job as the head of the Brand New Fully Equipped Cadillac Automotive Department there, and we did.

I was just so thrilled!

I met the daughter of this dealer. We were just down in Ottawa a few weeks and she phoned and asked me how we were getting along and asked me over one afternoon for tea. She asked me if I played bridge and I said, "Yes." And she said, "Well I belong to a four table bridge club and one of our girls is getting married and is going out west and we're looking for a new member."

I joined. I was just thinking the other day about how I'd get ready for sixteen people. It would floor me now. I'm worn out just getting a meal for myself. Anyway, we had some of the nicest parties. They were all professional people and I met some people I really liked. We took turns entertaining. I remember the Mayor's wife always entertained with such elegance. Her maid was always dressed in black and served us drinks on a silver tray. I wonder why I remembered that? And her mother was draped in ropes of pearls, she looked like the Queen's mother!

All Jerrold would say is, "Your friends are too fancy for me." We always had two sets of friends. I felt sorry for him in a way. He didn't even get out of public school. He tried the entrance and didn't pass. Then the First War came along and he was needed on the farm to help the war effort. He did pretty well for somebody with no education at all. Just a boy from a farm with no education. He was very edgy and unhappy when he was with people who were educated.

We never knew much about the depression. The 1930's were wonderful years for me. Oh, I think Jerrold got his pay cut by $5.00 a week so we didn't get new running boards for the new red roadster right away. We had a nice apartment with a big veranda and nice garden to use and there were such lovely stores in Ottawa. It is the Capital of the whole damn country. You'd wear a hat if you were out on the street and you'd always wear your gloves. It was only the crummy people that didn't. It didn't matter how hot the day was, if you were in Ottawa you wore your gloves. I had a lot of really good friends and neighbours. I was really flying high. I loved it. I just loved it.

We used to go down to the Shadow. They had a nice dining room there and a grill. They had an orchestra there all the time and you could dance between courses. They didn't bring things out on a tray, they had tea wagons that brought everything. Say you wanted scalloped potatoes and maybe pureed spinach, you could point at what you wanted, they'd put it on a plate and serve it. It was an awfully nice place to go. I had one of my birthday parties there.

Until the Second War came along everybody dressed like Mrs. Aster's plush horse. You had to have a hat and your gloves. You really got gussied up as the saying goes. By the middle of the war you could notice the difference. People would come in without hats or gloves and we would say, "Doesn't that look funny." People had always dressed in formal attire but I think the war changed a lot of things. But the war was later.

Before the war we went to a lot of nice nightclubs and we would always dress semi-formally. We went to Standish Hall which was a nice place, the Shadow of course, and Chez Henry's, that was a very nice hotel about on equivalent with the Shadow.

We bought the Pontiac convertible in Ottawa. I used to love that little red Roadster. I learned to drive in that car. I told Jerrold that I wanted to drive and he said that he didn't think that I was the type. And I said, "What do you mean 'Type to Drive'?" He took me around a parking lot on a Thursday and Friday and I got my permit that Saturday. In the summer I'd drive around with the top down shopping and visiting friends and going to movies and what not. I had a lot of fun with that car.

Movies were only twenty five cents. We used to go to about two movies a week. I just love to see the old movies. We grew up knowing all the actors and actresses. There was Betty Davis and the Barrymoores, Rock Hudson and Marlena Deitrich. They were really good actors in really good meaty stories. There wasn't any sex, just wonderful stories and we loved them. Now all the stories are is a whole lot of bed hopping going on. You know it's true. There was one that we just loved, Bing Crosby in Going My Way, did you ever see that? I'd get home from a movie and I wouldn't even stop to take my coat off. I'd be at the piano figuring out the theme song and I'd have it together chords and all in no time. I've always had a good ear.

Jerrold's mother and her sister would often come down and visit us in Ottawa. She said, "I'm so ashamed that when we first met you I thought you were just a little butterfly. My it's just a wonder what way you've taken hold. Why you can drive a car as good as a man. You take such excellent care of the baby and your home and your meals are lovely." And I said, "Grama, I hate cooking." I don't to this day like cooking. And she said, "I think you're a fibber because you never have uninteresting meals." Anyway she went back to Picton and told the neighbours. I was talking with Mrs. Carter and she said, "I'll tell you who is the favourite daughter in law in the Shortt family now. It isn't Bessy, it isn't Rhoda, it's you." And I said, "Oh no."

When I got pregnant again I was terrified after what had happened the last time. I went to see a well known and respected gynaecologist, Dr. Cargill, and I was almost in tears. I said, "Six years ago I almost died." And he said, "Don't worry, just leave everything to me. Your last doctor should have been strung up." He really looked after me. He put me on a weird diet. Apparently there are some kinds of food you can eat and they leave a beneficial ash in your body. He sure knew his Onions. About three hours after Ward was born I was sitting up in bed feeling great.

Jerrold said, "Don't think I'm going to stay home just because we have another baby around." I said, "We'll just have to because I don't want to leave a little tiny baby alone so what do you propose we do?" He said, "I guess we'd better get a maid." That's how the maid started. Rather than stay home with his own kid he'd rather have the maid take care of it. He was a funny man; he never wanted any responsibility. Everyone said he must be the most wonderful man to live with. He was everything but. He just wasn't what I'd thought he was. After we were married his mother used to say to me, "Jerrold is just like his father, he's no good at home with his family. He doesn't talk to me; we're never in the same room at the same time. He doesn't open his mouth but the minute somebody comes to the door he just glows; he lights up like a Christmas tree."

Jerrold was a result of how he was brought up. He grew up on the farm out working with his dad. The men did the outside work and the women did the inside work. And that was it.

So, Ward was the second. In the summer the maid used to take him down to the park everyday. They'd go down for some sun and some shade. When they came home I'd take off his little booties and his legs would be a little bit tanned. I remember he used to sit by the window and watch for Doug to come home from school. I'd say "Here's Doug." "Bug!" "Here's Dougie." "Buggy!?" He'd stand up and giggle.

While I undressed for bed, Ward would pull out the plugs of the bed lamps and watch them slide down the sides of the arched headboard. He got the biggest kick out of that. He'd say, "hee hee hee."

That's all anybody ever knew of him. He had a cold and his lungs weren't too good I guess. My father kicked his TB and went on to live to eighty three, but they say susceptibility to it runs in the genes I guess. Little Ward died of galloping TB. Today he would have lived but there was nothing anybody could do for him then. Jerrold and I were very very sad. It was some kind of absolute sacrifice. I dreaded going home in the afternoon to such a silent house. My neighbour meant well when she gave me two goldfinches, but it was the piano that helped me most.

We had a family doctor who was almost like a friend, Dr. Davies, we thought an awful lot of him. I told him that I wanted to adopt a baby right away. And he said, "You're a young woman, you'll have more children." I said, "I could never love another baby as much as I loved Ward." You know you always say that. I said it again when my second grandchild was to be born. Then the second baby comes along with a car load of love and proves you wrong.

Jerrold was always a big party lover. If there were a party he'd be all for going. Friends of ours, another young couple Bill and Flora McEnin, phoned us up as they'd often do and asked if we wanted to go to the Gatineau Club or the Shadow or somewhere. This was about six weeks before my third baby was due. I said, "Oh for heaven's sake, are you crazy? I can't go out like this." I just felt ugly and awkward. And she said, "Do you mind if Jerrold goes with us?" Well what could you say? "Oh yeah I do?" No. So I said, "Oh no I don't." So he ups with his hat and coat on and out he goes with them and leaves me sitting at home.

Jerroldine was the third one and she was born not quite two years after Ward died. Jerrold was tickled pink. When the doctor told him that it was a girl he said, "You're a darned sight better doctor than I thought you were." And I said, "I had nothing to do with it?!" He was so happy. He said, "Son of a gun it's a girl!" He was very happy to have a daughter. I was too, but if I'd have had another boy I wouldn't have been disappointed.

I liked boys. I'd have to be very careful around Jeri when she was a bit older. We'd be talking in groups about girls vs. boys and I'd invariably have to bite my tongue. I liked boys. If my first baby had been a daughter I'd have been sick. As for all my friends that had daughters, I looked down my nose at them. I don't know why I felt that way but I did. When Ward came along folks would say, "Oh isn't that a pity I bet you wanted a girl." And I'd say, "No I didn't." I hadn't had a daughter and I was satisfied with boys.

Jeri was a very pretty baby. People'd say they figured all babies looked squirmy and red and wrinkly looking. As a rule they do. But they'd say, "Son of a gun! She is a beautiful baby." We were very proud of her. Jerrold was always as strong as an ox; Jeri took after him. We brought her in to be checked by the doctor every week she was always extraordinarily healthy.

We got another maid when Jeri was born, Agnes Disarmo. She was a French girl of about sixteen. We didn't have her for long. We were in a triplex and my neighbour across the hall said that she would often hear the baby crying when Jerrold and I were out but never very often when we were home. She said, "Sometimes she'll cry for quite a while." I asked the other neighbours and they said, "Yes, sometimes that baby cries a long time." I had mentioned it to Agnes once and you know what she said to me? And laughed! She said, "Oh that's good for a baby's lungs." Good for a baby's lungs! I sent that bitch out the door.

We got another maid. My friends would ask, "Where did you find her?" I'd say, "I just phoned the employment bureau." And I had. My friends would tell me how lucky I was to have her and I'd say, "You don't need to tell me about Pearl Frazer; we know what a jewel she is."

She wrote us after she was married and said that she hoped that the next maid that we got would take good care of "My dear little hegg." She was French. She was French and Indian and my doctor said, "If you have got a French and an Indian friend, you have got a friend for the rest of your life. They are the most honest, lovable people on earth." She used to hug. She'd hug Jeri out on the porch we had that opened up off the living room, and the neighbours said, "Now when you're out she sits out there and she rocks that baby and she sings to her and calls her a dear wee thing." She took the mattresses off the beds every morning and gave them a wiskin' on the porch, when I asked her why she said, "Oh my mother always used to do that." Jerrold never sent his ties to the dry cleaners, she knew how to clean them. Oh, well, she was just something else. She made beautiful outfits; I was just the envy of all my friends. Jeri had lovely little petticoats under her dresses with all hand tatting on it and hand made sweaters, and hand made little crochet shoes and what not. We'd go out at night and we'd come back and there'd be another little pair of shoes sitting up on top of the radio. She'd say, "Oh aren't they cute?" And they would be. They'd be pale pink and they'd have embroidery on the toes. She was a real artist. She could draw. She could paint. I said, "Well the man that gets Pearl I'm telling you is going to get a prize." Well one did and he did.

After Pearl left, Jeri often asked me about her and I said, "I wish I knew." She phoned me one night while I had the bridge club over. It was a long distance call. You always used to say "long distance" if it were a long distance call years ago. When you herd "long distance" you were always afraid that somebody died. I said, "Long distance." And that was a shocker. Everybody muttered, "Long distance! Long distance!"

She said, "Oh! is that Mrs Shortt?" And I said, "Yes." And she said, " Oh! I'm so glad you're not dead!" Apparently her husband had seen a death notice in the paper and the name was Shortt. I guess she must have been near out of her mind. Of course I didn't know what she meant.

The last I've heard she was living in Quebec; she phoned and said she was going to come up because she wanted her children in Ontario schools. I've never heard from her since. I never had a friend any better than Pearl Frazer. Pearl Hence her name is now.

Jerrold got talking around town and found out about a nice little grey house in the west end near Island Park drive. The whole area was nice what with well kept homes, nicely kept lawns and flowers and everything. We rented it. After sixteen years of an ice man running in with a big slabs of ice dripping all over the place and an ice box overflowing all over the floor I was thrilled to have a Frigidaire.

We had a dog. I think they call them Rat Tailed Terriers. They are black dogs with brown markings, skinny skinny, nervous, jumpy dogs. I liked to use sour milk for baking cakes and at that time you didn't have freezers to freeze the stuff so I put it down in the basement where it was quite cold. We went out one day and put the dog in the basement. We came back and the dog had pulled down a sweater at the top of the steps and chewed it and he had toppled the sour milk all over the floor. To finish the job he took a leap and went through the screen in one of the little basement windows. One of our neighbours saw him going down the street and got a hold of him! He was a wild thing.

We had a cat given to us. It was an Angora. Oh it was a gorgeous thing with big green eyes. He was a skinny animal but he looked big in all that pure white fur. But we had coal in those days for the furnace; he'd go down in the basement and he'd crawl all over it and I wish you could have seen him. There was a washing powder in a big box years ago, it was like Tide but they called it Rinse-O and I was forever washing him with that. He was the worst looking thing you ever saw when he was wet. I'd towel him off and Jerrold would take a side out of a cardboard box and we'd sit him in front of a register. We were always loosing him. He'd be out and the neighbours would find him. I don't know what happened to him finally.

We rented a cottage out on Lake Dechenes. I used to drive out to it on the Prescott highway with friends. They all swam but me. I'd just wade around by the shore. Hugh called from the raft where he and Corra were, "Come on out Gwen!" And I said, "You know I can't swim." He said, "I didn't know you couldn't swim. Everybody can swim!" And I said, "My husband told me that he didn't think that I was the type to swim." He said, "Awe for god's sake." He came over to where I was where the water was about half way between my knees and my waist. He said, "You know if you fall down in it you can get up eh?" So anyway, he taught me to float in about two minutes. He'd hold his hands under my stomach and say, "Kick your legs and your feet." I was swimming!

I went back in town to pick up Jerrold from work and said, "You know I can swim?" And he said, "Yeah I bet." I said, "I can swim!" I called Hugh and Corra to come back out that night. I said, "He won't believe that I can swim!"

There was a woman who had a cottage near ours, Gwen Morris. In the summers our husbands would be at work and we would stay out at our cottages. We would do everything together. She would come over and we would do my housework then we'd go over and do her's. We'd swim together and boy could we talk. We'd sit around and talk for hours. I never smoked before that. She'd ask me if I wanted a cigarette and I'd say, "No, I'm not too fussy about smoking." And she'd say, "Awe come on, I don't like to smoke alone." So we'd talk and smoke. By the end of the summer she said, "You know, you're smoking more than me." And I was. The habit didn't stick. I'd buy a package and I'd smoke so few that they'd be in my purse for a month or two. Jerrold would see them and say, "Those aren't good for anything, they're stale!" They would be too.

The first twenty-five, thirty years of our marriage were good. We went to a lot of dances and social affairs. I'm glad Jerrold and I did a fair deal of touring. Jerrold knew a man, who made this contraption that was the grand daddy of the campers. We rented it one summer and went up to Clear lake which is up near Peterborough with another couple, Mel and Edith Mason. We'd hook this thing up to our car and it would trail behind. You'd pull the back half up when you were on the road and it would just look like a big box. We'd let it down at night and it had a full size mattress in it with a spring and everything else. The guy just thought it up out of his own head I guess. We built a fire place out of a bunch of stones and put a sheet of tin on top. We could cook a whole dinner with beans and bacon on it. Another summer we went up on a steamer to Lakefield where we rented a boat and we used to tour all through the islands. In the 50's we'd spend summers in Vermont. Vermont is so beautiful. I often said that if Jerrold died first I'd move to Vermont. I enjoyed our excursions.

I was reading Reader's Digest and they had a questionnaire and one of the questions was, "What would you do if you had $10,000.00?" I checked off travel and the answer said that I was the aesthetic type. I love travelling. If I had money I wouldn't spend it on the house or clothes I'd spend it on travelling. I would have liked to have done more travelling but in my day but almost nobody went very far. If anybody went to Europe you'd think they were at the right hand of God. The only time I ever went anywhere without Jerrold I went to Africa. Africa! I think that that may have made up for all the travelling I didn't do. I'm too old to travel now. It's a struggle just getting out of the bathtub.

Once we drove down along the St. Lawrence to Quebec City. I think Jerrold was bored. I'd want to stop and look in little shops and he'd just sit in the car. I wanted to go up and see the Plains of Abraham. I'd read about what happened there and I wanted to be there and walk around. Jerrold said, "Why the hell do you want to walk around in a bunch of old fields?" He couldn't understand me at all.

As life went on I'd be working or busy with the kids and Jerrold would go hunting or fishing with friends. Sometimes they'd fly way up north in a little plane and ski around. I'd pack food for them and off they'd go. Later I found out about other women. Sure it hurt, it hurt bad but what could I do? I couldn't tell anybody. I was so embarrassed. I'd cry on my own. I'd try not to think. He just wasn't the man I thought he'd be.

We didn't have money or social position or anything else but I had the right values to pass on to my children. I remember Jeri used to come in and she'd say, "Can I have a cookie?" And I'd say, "No." And she'd say, "Well you just made some." And I'd say, "MAY I have a cookie?" And she'd say, "What's the difference?" And I said, "You know you CAN have one; I'm not going to say no. The right thing to say is 'May I have a cookie'." I never had much of an education but I read a lot of books. You can learn a lot from reading.

From the time he was eight Doug always wanted to fly. He was forever making little planes out of balsa wood and I wasn't allowed to tidy the mess of glue and sticks, "Method in the Confusion, Mother." Jerrold thought the profession to be far too risky but Doug persisted. I understood; I always wanted to play the piano.

Jerrold just about had a fit. He said, "He joined up at seventeen and a half. Why couldn't he have waited until he was eighteen?" Doug said he wanted to join up before he had to go. He said to me, "How do you feel about it?" And I said, "Well, I've never known anyone personally who ever flew. Maybe if I were to pick a job for you I'd want one that to me seemed safer. But that's all you've wanted to do since you were eight years old. Your dad should have been ready for it. If it's what you want, I'm happy for you." You can't live other people's lives for them. I said to Jerrold, "It's his life. Not ours." Doug said, "If they hadn't accepted me for that pilot's course I don't know what I would have done."

I remember the day that Doug was leaving in a taxi. Jeri was out playing after school and I hunted and hunted but couldn't find her. When she came in I said, "Jeri, you knew that Doug was going to Nova Scotia this afternoon and you weren't here to say good bye to him." And she just looked at me and said, "I don't care." Of course she was only eleven then and full of herself as kids that age generally are.

I saw our minister after Doug left home. I said, "I'm worried about him, he has lived such a sheltered life and now he's going right from school bang into the service." He said, "Well, if you never had any trouble with the young lad, don't ever expect to. Water finds it's own level. When kids are brought up properly, the friends they choose are the right kind." He had never brought anybody home who we didn't like.