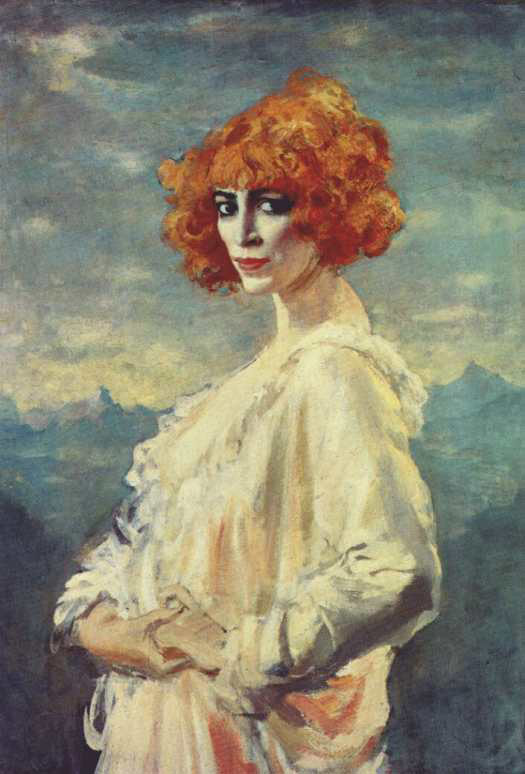

The Marchesa Casati

portrait by Agustus John

Simply seeing The Marchesa Casati is wonderful; there was obviously something very special about her and the way she was beheld by Augustus John. There are conspicuous allusions to the Mona Lisa of Leonardo Da Vinci, they both loom over an elemental landscape, address the viewer with their eyes, and reveal something more than a mere physical presence. Whereas the Mona Lisa can be said to have a subtle expression (Janson 352), The Marchesa Casati has a bold attitude; the Marchesa is no renaissance model, she is a modern woman.

She does not sit patiently and perpendicular, she stands. Her impatience can be seen in her face but more so in her fidgeting hands and diagonal posture; evidently she is a vibrant woman with her own agenda. Her eyes, which look directly across at the viewer, are well above the horizon; thus she and the viewer share the visual power of elevation. Her pyjamas are dainty, but rendered with bold decisive brush strokes. They obscure her body sufficiently to put emphasis in her hands and especially her face, but not so much as to render her unattractive or modest. Her hair is thick and fiery, almost as crimson as her lipstick, and it bounces out from the picture plain by contrast with the turquoise sky. She has indisputably taken control of her wild hair as can be seen by her black eyebrows. Her neck is disproportionately big, physically holding her head well above her body, perhaps thereby symbolically holding her intellect well above her physique. Of all the empowering devices, her eyes are the strongest; unlike the innocent little eyes of the Mona Lisa, the Marchesa's eyes are gigantic and shining with life, wide open and ultra-perceptive. The lines of the pyjamas, arm, and neck direct the viewer's gaze to these eyes. The most striking thing about her power is that it is in no way derived from any masculine pretence. She is a powerful woman.

In fact, Augustus John wrote this (John 239-40):

One day I was present at a thé dansant at the house of the Duc de Gramont. This enormous house on the Champs Élysées had the aspect of a fortress. In France, tea is always accompanied by the alternative of port - white port. I was helping myself to a glass of this when a new arrival arrested my attention. A lady of unusual distinction had entered. Her bearing, personality and peculiar elegance seemed to throw the rest of the company into the shade,... Even the Duchesse, whose natural style of beauty was unassailable, looked, by comparison, somewhat rustic. The newcomer wore a tall hat of black velvet, the crown surrounded by an antique gold torque, the gift of d'Annunzio; her enormous eyes, set off by mascara, gleamed beneath a framework of canary coloured curls. Instantly captured by a gentleman who remains anonymous, she moved round the ball-room with supreme ease, while looking about her with an expression of slightly malicious amusement. Our eyes met... Before leaving I obtained an introduction; it was the Marchesa Casati.

The Marchesa Casati was outrageously wealthy, in both money and vision. She was the soul heiress of two fortunes, and was what Cole Porter, "moving currently in the same set, called the `rich rich' (Easton & Holroyd 80)". In 1901, at the age of 20, Luisa Amman was Italy's wealthiest heiress. She married Camillo Casati Stampa di Soncino (1877-1946), "scion of one of Milan's most ancient and aristocratic families (Wistow 4)". They owned a country estate at Balsamo, apartments in the Palazzo Casati at Milan, a hunting lodge known as Castello di Cusago, and a villa in Rome (Wistow 4). Around 1902-03 at a Milanese hunt, she met the passionate Italian symbolist writer Gabriele d'Annunzio - this meeting was to change the course of her life (Wistow 4):

This forty-year-old "Prince of Decadence," as he was called, was instantly inflamed. An article in Ruy-blas (May 1905) suggested that their relationship had advanced to a point where d'Annunzio was, rather unrealistically, considering betrothal to the Marchesa, although both were Catholic and married....Together they conspired to transform reality into "something rich and strange."

It was during this time that she transformed herself into the famous La Casati. She acquired the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni in Venice, a wide one-storey structure on the Grand Canal which now houses the Peggy Guggenheim Collection (Wistow 4):

...its impressive entrance terrace, eighteen enormous stone lion heads (hence the name), and large over grown garden, with white peacocks and albino blackbirds dyed blue flitting amongst gilded trees, provided the proper stage for the Marchesa and her many theatrical triumphs, culminating in the great pre-war balls. Conveniently, d'Annunzio lived directly across the canal in "La Casetta Rossa". It may have been purchased by the Marchesa for his use, just as later, in 1921, she acquired the Villa Cargnacco on Lake Garda and presented it to him as a gift.

In 1914 the Marchesa and her husband officially separated, and a decade later she became the first Italian divorcee. "The duration of the war she spent in Venice and then in Rome, where she, d'Annunzio, and a magician used to raise spirits at night on the Appian Way (Wistow 5)". In 1919 she encountered Augustus John in Paris, where his two portraits of her were executed (Wistow 5).

La Casati was a keen supporter of the arts, and an artist herself. Alberto Martini refers to the Marchesa's activities as poet in Alberto Martini: Mostra Antologicas (218; Wistow 9), also, Peggy Guggenheim refers to her as poetess in Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict (334; Wistow 9). La Casati was an ardent enthusiast of the Futurists, and a primary muse. She inspired Martini's famous cover design for the Futurist journal Poesia, and collaborated with Fortunato Depéro to create Il Giardino Zoologico, a theatre piece for marionettes to music by Ravel (Wistow 7). Marinetti dedicated the portrait of himself by Carlo Carrà (on an actual piece of paper which he stuck to it) to "the great futurist Marchesa Casati with the languid, satisfied eyes of a jaguar that has just swallowed the iron bars of its cage" (Wistow 11).

She played, as muse, a prominent role in the writings of d'Annunzio, Milanese poet Brunati, as well as in a novel by Elinor Glyn (Wistow 7). Her moral and financial support of the Ballets Russes was substantial. Diaghilev, Nijinsky, and especially Bakst often visited La Casati in Venice. "Indeed, the Marchesa's Venetian palace provided the setting for one of this century's great dance moments when Nijinsky was introduced to Isadora Duncan, and the two danced together impromptu (Wistow 7)". La Casati herself "is known to have danced in public for the Red Cross in Rome around 1916, wearing little more than a black velvet rose, and later may well have taken part in Marinetti's Futurist ballets (Wistow 7)". She commissioned from Bakst numerous costume designs for her bals masqués, outrageous "everyday" wear, and portrait studies (Wistow 8):

The Paris magazine La Ville Heureuse in 1913 mentions three costume balls and ten processions orchestrated by Bakst on the Grand Canal and in the Piazza San Marco in just six weeks. His ability to create breathtaking coup de théâtres was inexhaustible....They could require weeks or months of preparation, not just for the design and execution of costumes and decorations, but for the actual choreography of the events, often including dance, music, and poetry readings, with their numerous obligatory rehearsals. For her such events were pure art; perhaps only a rock performance today could approximate their drama and extravagance.

Of course, La Casati was always the focus of these events (Wistow 9):

Like many performance artists of the 1970s her body, face, hair, and clothes became a primary means of self-expression, if not the ideal vehicle for fully realizing her deepest fantasies; she might appear as an animal tamer, Pulcinella, Scheherazade, or Count Cagliostro - Luisa Casati transformed herself into an art object....In pink brocade trousers à la sultane, with a mauve or green wig, or hair dyed black or striped like a tiger's, she took to the streets encircled by her menagerie of cheetahs, borzois, greyhounds, monkeys, and parakeets.

Judith Thurman mentions in her biography of Isak Dinesen (a pen name of Baroness Karen Von Blixen) that the Baroness once travelled in Europe with two pygmy porters who carried her umbrella and handbag, but her theatrics were criticised partly because this had already been done by the Marchesa Casati (?).

La Casati had over 100 portraits done of her, over 75 of which are extant. "Together these images composed a singular portrait gallery, in actual fact filling an entire pavilion adjacent to her Paris mansion....There is even a `portrait' of her foot by Charles Chaplin.... - in style and mood they embrace Symbolism, Academic Realism, Cubism, Futurism, Fauvism, and Surrealism, together with others which presently bear no proper nomenclature,... (Wistow 10)". Works were done by many artists including Man Ray, Giovanni Boldini, Alberto Martini, Umberto Boccioni (illustration in Vogue, Sept 1, 1970), Lolo (Julio) de Blaas, Ignacio Zuloaga and Leon Bakst. "La Casati may also have approached such artists as Giacomo Balla, Mikhail Larionov, and Kees van Dongen, for her taste was bold. But she may equally have been solicited by them, as was the case with Jacob Epstein (Wistow 10)". When Martini complained that she never allowed him to exhibit his portraits of her for money, she said, "What is fortune compared to the dignity of art? Nothing!" (Wistow 11).

Very often, the Marchesa would have a hand in the creation of her portraits (Wistow 11):

Just as in some cases Luisa might allow the pendulum of artistic freedom to swing in the painter's direction,in others she could equally insist on directly affecting the creative act....Obviously La Casati and her portratists had much to gain through cooperation: their conspiracies could be mutually profitable.

In 1919, after two years as a major in the Canadian Army with the job of documenting the Canadian war effort in Europe, Augustus John returned to France. He had been requested by the British Government to paint portraits to commemorate the Peace Conference there. Shortly after his first encounter with Luisa Casati, she was "added to John's list of sitters and, briefly, of lovers (Wistow 13)". "Favourable reviews were forthcoming from all quarters, and a laudatory article in The American Magazine of Art (May 1920) was fittingly accompanied by reproductions of Sir Robert Borden and La Marchesa Casati (Wistow 13)". (Wistow 15):

The Marchesa's comment that John "painted like a lion" is perhaps the highest form of praise, given her fascination for members of the feline community. Tinged with sexual innuendo, the statement provides a valuable clue in assessing the Toronto painting - a product of true collaboration between portraitist and sitter. Its vigour, its energy, its potent verisimilitude derive in large part from the mutual fascination and sensual attraction of the two. Theirs was a meeting of equals.

Peggy Guggenheim mentions in her autobiography that, "Capri itself is like an enchanted island....the Marchesa Casati [had] roamed about the island with a leopard (32-33)".

Unfortunately, between art, villas, pets, entertaining, and travel, La Casati disposed every last cent of her enormous fortunes, and then some (Wistow 5):

One source estimates her debts in 1932 to be the modern equivalent of twenty million dollars. Her impending bankruptcy, at least in the mind of the Archbishop of Paris, Cardinal Louis Ernest Dubois, was just retribution for her profligate lifestyle. When she requested a visit by him to plead forgiveness, the priest was confronted by La Casati dressed all in white, carried in on a settee by four valets, holding a white gladiolus on her lap while a white parrot, representing the Holy Ghost, perched near her feet. With a transfixed stare she kept repeating: "Je suis la Vierge immaculée!"

By December 1935, all of her properties and the vast majority of her amazing collections had been sold to satisfy her creditors. She was arrested and sent to prison for two years, but the sentence was reduced to two months. She then fled to England where a few faithful friends supported her (Wistow 5). "The Marchesa having lost every penny of two fortunes, he [Augustus John] made a permanent contribution to her wants by banker's order (Easton & Holroyd 80)". (Wistow 6):

During the two decades before her death, the Marchesa lived at over fifteen different locations in London, including, for a period in 1944, John's own house on Tite Street. Most were boarding houses into which she crammed her four Pekingeses, a stuffed lion's head from Portobello Road, a cuckoo clock, a television, several scrapbooks, and her black magic paraphernalia. Besides bee juice from Harrolds and gin, she survived on stimulants such as belladonna, cocaine, and opium, and often went hungry.

She died at hospital, destitute, in 1957 (Wistow 6):

After making new eyelashes and bringing white carnations for her, a friend managed to sneak into the Marchesa's coffin her stuffed Pekingese.

Augustus John remained a close friend of Luisa Casati to her death. He executed a third oil portrait of her probably in 1942 which is now at the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff (Wistow 14).

"Described by Lord Duveen as an `outstanding masterpiece of our time', the Toronto portrait passed to the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1934 for £1500.00 (Easton & Holroyd 80)". As Wistow so aptly concludes, The Marchesa Casati (16):

...clearly communicates that woman is a sexual being seeking not so much the power to seduce, dominate, or betray, but rather the right to enter into dionysian pleasures as an equal, and more, to initiate such pleasures.

Whereas the Mona Lisa clearly "embodies a quality of maternal tenderness which was to Leonardo the essence of womanhood (Janson 352)", The Marchesa Casati clearly embodies the powerful qualities of imagination and independence which Augustus John loved.

Works Cited

Easton, Malcolm & Holroyd, Michael, The Art of Augustus John, Seckert & Warburg, London; 1974.

Guggenheim, Margaret, Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict, Universe Books, New York; 1979.

Janson, H.W., History of Art, Abrams, New York; 1973.

John, Augustus, Chiaroscuro: Fragments of an Autobiography, Johnathan Cape, London; 1952.

Thurman, Judith, Isak Dinesen: The life of a Storyteller, (?).

Wistow, David, Augustus John: The Marchesa Casati, The Art Gallery of Ontario; 1987.

-

I have heard since that La Casati, when her fortunes were almost gone, went to New York to meet an American millionaire. She arrived at the restaurant where they were to meet with boa constrictor wound around herself - he immediately ran out the door.

-

Apparently she would use barbiturates to sedate her larger pets - lions, cheetah's, tigers, etc.

-

Apparently she hired men to stand, practically nude, on either side of the entrance to at least one of her balls. They would fan the guests as they entered with imported palm frons.

-

And more from John's autobiography (240):

The Marchesa became a frequent visitor at Tony's parties and it wasn't long before I added her to my list of sitters. Only once have I met a comparable example of this genre of Italian femininity: this was the Contessa Bosdari, whose husband was Italian Ambassador when I visited Berlin. In both cases, a rather fantastic exterior was accompanied by a perfect naturalness of manner; a naturalness which, with the Marchesa, sometimes took on a thoroughly popular note: she had borrowed from the colloquial some important additions to her vocabulary, which, used with judgment, considerably enhanced her powers of expression, more especially when these were employed in the dissection of her friends' characteristics, mental, moral and physical.

-

La Casati's only child was brought up by her father, disowned her mother, and became a chartered accountant.

-

With the last of the funds La Casati could lay her hands on, £15,000.00, she threw one last ball before going to prison.

-

Apparently a love poem exists in the John family archives entitled "Casati at the Alpine Club," in which the artist compares the Marchesa to a star which, seeking freedom, rises above the mountain summits.

-

The first portrait was probably abandoned because it was too obviously like the Mona Lisa (seated and perpendicular) to begin work on the more successful second.

-

During the last years of her life she smoked marijuana.

|